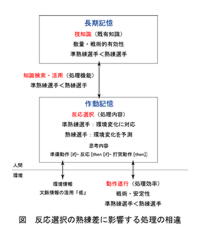

Presentation topic: The process of acquiring technical knowledge in kendo Presenter text by Okumura Motoki (Tsukuba University) Venue: Surugadai Campus, Meiji University Presentation proceedings This paper assesses the processes involved in developing the gresponse selectionh used in kendo to determine what movements will be executed and how they will be executed. Response selection in sports can be passive or instantaneous (dependent on the environment), or may alternatively be based on the use of previously acquired knowledge to actively induce changes in that environment. The former of these two (passive response selection) has been the subject of much research. However, little investigation into active response selection has been carried out. In this paper previously acquired strategies and technical skills (that is, previously acquired technical knowledge or skills\hereafter referred to as PATK), and their utilisation by college level kendo practitioners, were the focus of my research. Differences in proficiency in response selection due to PATK, execution ability, and reasoning were examined by means of four different experiments. First, I examined the differences in proficiency levels in terms of the structure and volume of the technical knowledge that the subjects already possessed (PATK). I divided the subjects into three groups of five as follows: Group A, non-proficient subjects (with approximately 10 years of competitive experience); Group B, semi proficient subjects (with approximately 15 yearsf experience); and Group C, proficient subjects (with approximately 15 yearsf experience). Each of the subjects completed a questionnaire and participated in a laboratory experiment to ascertain what technical knowledge they consciously employed when selecting responses during training and matches. The results indicated that subjects in all three groups organised their PATK into brief procedures (of three or four steps) in accordance with the allotted match time and the limits of their operational memory capacity. Also, the higher the level of proficiency, the more knowledge subjects possessed in regard to the tactical moves and responses that they themselves executed or that their opponents executed, such as feints. This was a factor in the way they organised their techniques (Group A\approximately 59%, Group B\approximately 70%, and Group C\approximately 84%). This understanding also contributed to an increase in the number of techniques in their PATK repertoire. (For example, the average number of different men attacks was 5.8 for Group A, 8.0 for Group B, and 12.6 for Group C). Furthermore, using tree diagrams I discovered that the combination of this knowledge served to produce an elaborate PATK structure before the last step of actually executing the technique was reached. It is clear that knowledge acquisition and the functions involved in utilising that knowledge are different. With this in mind, I investigated the proficiency differentials in execution efficiency as it relates to the utilisation of PATK in response selection. First, I created two groups of eight subjects: Group A (semi-proficient, with approximately 13 years of competitive experience) and Group B (proficient, with approximately 14 years of competitive experience). Before conducting the experiment I first confirmed the PATK and athletic ability of each subject. I designated the type of response selection available to counter an opponentfs attacks. Results showed that there was no difference in the level of proficiency in regard to the utilisation of concise thought actions (preparation, reaction, and attack) and contextual information. However, Group B demonstrated a higher level of utilisation of PATK (Group A, approximately 50%; Group B, approximately 75%), their times showed greater efficiency (Group A, approximately 10.2s; Group B, approximately 6.7s), and their scores showing technical ability were higher (Group A, approximately 19.6 points; Group B, approximately 29.5 points). The difference in proficiency in utilising PATK was due to the fact that Group B subjects actively employed PATK and decided beforehand what they would do, often demonstrating pre calculated response selection. Furthermore, the frequent use of PATK gave rise to repetitive learning competence, and this led to an improved functional ability to utilise this knowledge. In addition, the differences in time efficiency and points scores for technical ability can be accounted for by the response selection and execution of the Group B subjects, who were able to demonstrate an ability to endure changes in the environment brought about by attacks by their opponent. In order to confirm differences in proficiency in a given environment, I tested the subjects in a match situation. I divided the subjects into two groups of nine: Group A (semi-proficient, with approximately 12 years of competitive experience) and Group B (proficient, with approximately 13 years of competitive experience). After ascertaining the PATK of each subject, I pitted the two groups against each other in a match. The results were as follows: frequency of PATK application, Group A, approximately 45%; Group B, approximately 70%; accuracy\the average time for the opponent to initiate defence relative to the completion of a successful or unsuccessful attack (0ms)\for Group A, |37ms when attack was successful and |210ms when attack was unsuccessful; and for Group B, |26ms when attack was successful and |141ms when attack was unsuccessful. These results showed similar tendencies to Experiment 2; however, the difference in time efficiency was eroded (for Group A, approximately 5.1s; for Group B, approximately 4.2s.) The disappearance of the disparity in proficiency and the faster times by both groups were an indication of the strict time restrictions inherent in a match situation. These restrictions and the difference in proficiency seen in execution of PATK and accuracy underscored the importance of selecting responses by applying PATK actively for predictive purposes and of improving functional execution in order to be able to apply skills swiftly, just as Experiment 2 had done. Players without a significant repertoire of PATK do not have the required knowledge to excel in matches. It can thus be surmised that in their case the frequency of knowledge utilisation would probably be low. With this point in mind, I tested whether the acquisition of PATK which could be useful in matches would improve response selection. In order to do this, I subjected the semi proficient group (whose members had approximately 13 years of competitive experience) to three weeks of training in recognising the PATK demonstrated by the proficient group in Experiments 2 and 3. Afterwards I made the two groups engage in a further match. Following the training period, a questionnaire was completed by six members from each group (the control, match observing, and knowledge acquisition groups), which showed that utilisation of PATK in response selection by the knowledge acquisition group had increased by approximately 15% (pre training, approximately 53%; post training, approximately 69%). Effective response selection had also increased, by approximately 10% (pre training, approximately 41%; post training, approximately 53%). There were also six categories of newly acquired technical knowledge, and as much as 50% of response selection was based on this knowledge. Furthermore, match analysis demonstrated that the attack success rate was boosted by a rise in the rate of successful initiation of defence 100ms or more before the completion of the opponentfs attack (pre training, approximately 32%; post training, approximately 42%). These results prove that training to acquire PATK\even for a short time period\has a positive effect on response selection. The improvement trend also verifies the findings of the first three experiments regarding the process for improving response selection. I have reached the following conclusions about the requirements for developing response selection in kendo: it is beneficial to acquire concise but elaborately structured technical knowledge which is diverse and practical; this knowledge should be applied actively in a competitive environment and the habit should be cultivated of choosing appropriate responses based on calculation; it is important to improve efficiency in execution in order to put convoluted knowledge patterns into practice successfully. Kendo competitors and instructors must be able to understand the processes of acquisition of technical knowledge and adoption of response selection. By using the findings of my research and comparing results, we can attempt to create concrete learning indicators and evaluation criteria for response selection. I would like to express my most sincere gratitude to Professor Yoshida Shigeru, who acted as my supervisor and was my long time instructor at Tsukuba University, and to numerous other people who assisted in the completion of this thesis. |